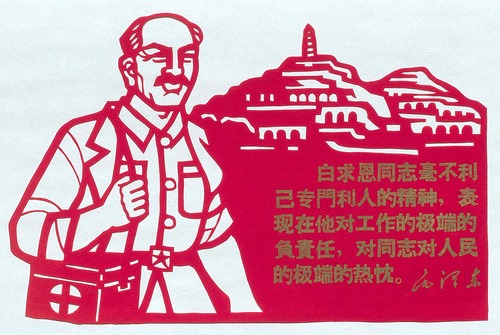

‘Norman Bethune,’ by Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library [flickr.com/thomasfisherlibrary]. License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

This is an opportunity to showcase the benefits of this Eastern healthcare system. But I think it may be the wrong direction, or at least a speed bump on a road towards progress.

China aims to further integrate TCM and Western medicine—in one way—by “creating new drugs.” This drug development will be based on a guideline described by China Topix as “indigenous intellectual property.”

Such intellectual property is not explicitly defined. But it sounds a lot like a reference to Chinese herbs and classical herbal formulas. The remaining step, it seems, is to “pharmaceuticalize” Chinese medicine.

The present initiative is akin to the 1950’s communist period when Mao Zedong westernized Chinese medicine to create what he termed, a “New Medicine,” which became known as “Traditional Chinese Medicine.” The change was driven more by economics and politics rather than any health initiative. [footnote]

One example of this less-than-exemplary change is that the Communist Party redefined acupuncture points with functions and indications, as if they were Western drugs. This superseded the classical view of acupuncture points as designations along connective tissue planes that integrated movement and performance of the entire body. The negative effect is that specific acupuncture points are now often selected to treat specific symptoms rather than address the body as a whole.

When one paradigm supersedes another while addressing integration, it is the modern equivalent of Mao’s New Medicine. It is the extinguishing of one medicine for the sake of another, not necessarily to benefit health. Therefore, while improvements in medicine are always welcome, one should be wary of contemporary buzzwords such as integration and innovation.

Footnote:

For more reading on the communist enactment of Chinese medicine, reference “Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China,” by Kim Taylor. Access my full summary of the book here.